Zena Posever was born an artist. Early on, the public schools singled her out for special art instruction. After high school, she continued her studies at several Philadelphia art schools and colleges and informally at the Graphic Sketch Club. Life studies and figurative abstractions fill her early sketchbooks.

In 1937, Zena became a scholarship student at the premier art school in America, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, which provided classical training as in Europe. Her teachers included the preeminent portrait sculptor Walker Hancock, drawing master George Demetrios and Albert Laessle, medal sculptor. Zena's large- and small-scale sculptures demonstrated control of anatomy and mastery of composition. Among her subjects were refugees, workers and their families, and musicians, reflecting her sympathy for struggle and love of creative expression.

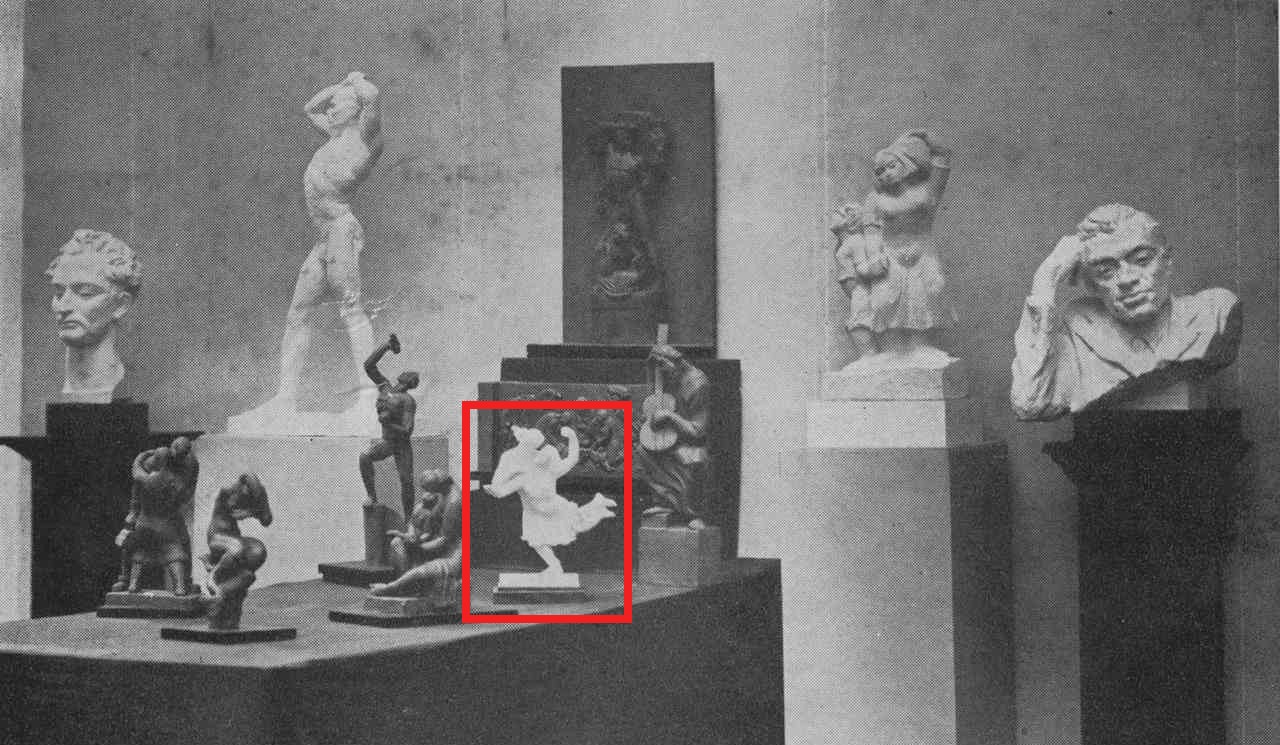

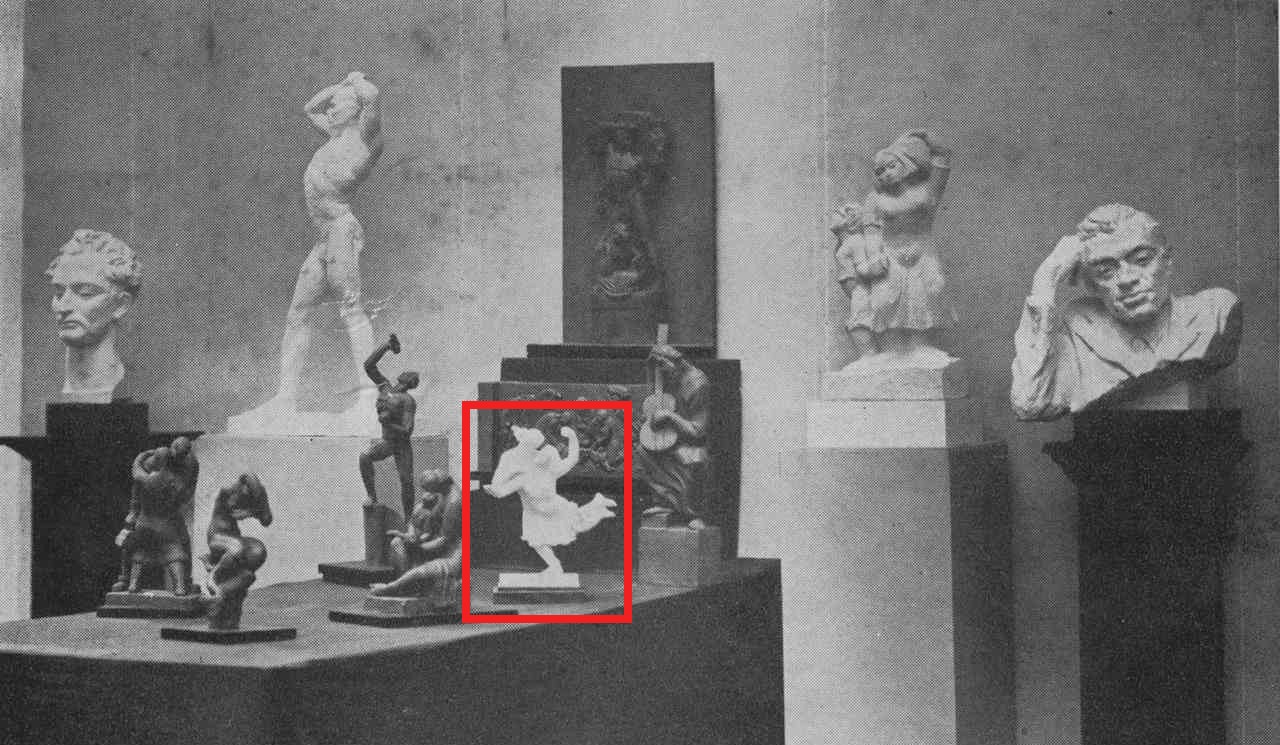

Her Favorite Sculpture

Play, 1939-40, an analogy of the happy childhood years spent with her sister, was Zena’s favorite sculpture. It suggests their warm relationship until teenage years. Her companion and playmate, a year older than her, was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and the family spent a decade looking for help before she was institutionalized. This sculpture was Zena's outlet for her first great loss.

Play, Bronze, 1939-40

Two girls in simultaneous motion gaze adoringly at each other. Their flowing hair, ruffled skirts and fulsome limbs touch. The rhythmic sculpture melds their bodies into one.

Picasso: Forty Years of his Art, "The Race" (1939 Exhibit Catalog Cover, detail)

The idea for the composition came after Zena’s visit to Picasso’s first American retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The Race on its catalogue cover, captivated her. Zena's sculpture shares its impluse, which is both classical and modern. His unparalleled abstract mural Guernica, affected her in another way: it had tremendous relevance in her life.

Picasso began his anti-war response in 1936, days after the carpet bombing of the cultural capital of the Basque region by the German Luftwaffe. It was the prelude to World War II. The Guernica mural represented the unimaginable horror of modern warfare. Zena’s husband of one year had gone to Spain as an American volunteer with the international brigades to fight against Franco’s Nationalists. One month after he arrived, a sniper shot and killed him.

Zena paid homage to the fight of the Spanish people and her personal tragedy with many visits to the Picasso, which remained in New York as a refugee until the return of democracy to Spain forty years later. The human tragedy of war, so close to Zena, affected the course of her life and remained a powerful influence in her art.